In 1877, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt died, leaving bulk of his 100 million dollar fortune to his son William Henry. His nine other surviving children were, to put it mildly, less than pleased. Bitter ruptures between the siblings ensued, resulting in acrimonious lawsuits over the late Commodore’s will. William Henry eventually settled with his brothers and sisters, but the experience left a deep mark. When he died a mere eight years later in 1885, not only had he more than doubled his inheritance, leaving an estate worth 200 million dollars, he preserved the harmony amongst his own children. His will provided for a much more equitable (if not exactly equal) distribution of his fortune between his eight sons and daughters. Upon receipt of their Croesusian windfalls, they embarked on collective spending spree, each lavishing huge amounts of money on elaborate and often times multiple country estates, many of which survive to this day. These monuments to the gilded age include Biltmore, the Breakers, Marble House, Shelburne Farms, and Hyde Park.

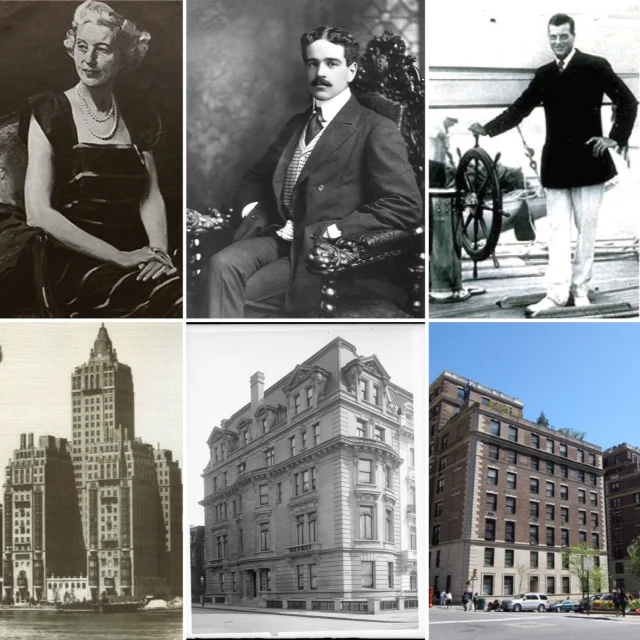

It is interesting to note however, that even before the Vanderbilt brothers and sisters became immensely wealthy under the terms of their father’s will, each (except for the youngest son George) already possessed a magnificent mansion in New York City, courtesy of the their father’s largesse. These elaborate townhouses, primarily located on Fifth Avenue between Fiftieth and Fifty-Seventh streets, (giving rise to that district being dubbed “ Vanderbilt Row”) were given as gifts from their father (or in the case of the two eldest sons, built from legacies left to them in their grandfather’s will). The paperwork for the construction of several of them was filed within months of the settlement between William Henry and his own siblings. Whether William Henry’s generosity was the result of fatherly love, or Solomonic wisdom, the results were splendid. To follow are pictures of his eight lucky children and their Fifth Avenue homes.

The Two Elder Daughters

Margaret Vanderbilt Shepard

Margaret Vanderbilt Shepard Emily Vanderbilt Sloane

Emily Vanderbilt Sloane 642 Fifth Avenue and 2 West 52nd Street

642 Fifth Avenue and 2 West 52nd Street

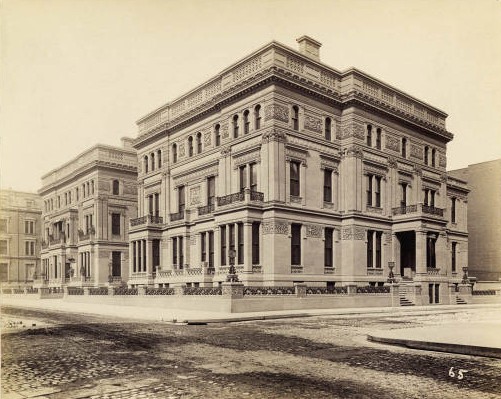

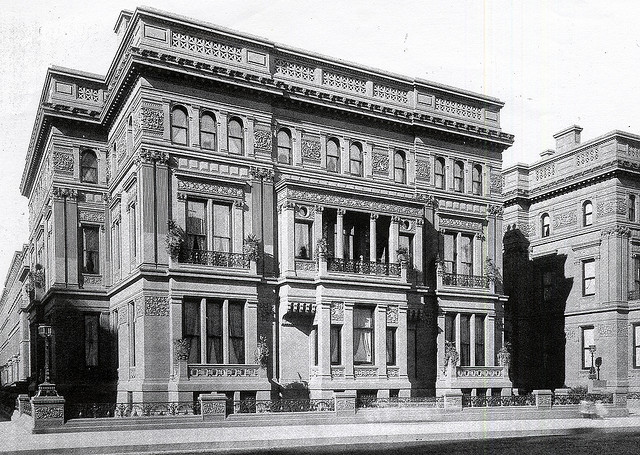

William Henry had the architect John B Snook design a double townhouse for his eldest married daughters, Margaret Vanderbilt Shepard and Emily Vanderbilt Sloane on Fifth avenue between 51st and 52nd streets. The two homes completed in 1882, were housed in a single pavilion, appearing to be one enormous mansion to the casual passerby. This was done in order to balance the gargantuan pile that William Henry was erecting on the southern half of the block, creating a unified urban place complex. Mrs. Shepard’s front door was faced 52nd street, while Mrs. Sloane’s faced her parents’ and was accessed via a mid-block vestibule shared with her father’s mansion. Whether this was by chance, or design I am not certain. It is recorded though, that Mrs. Sheperd’s husband at times exasperated William Henry Vanderbilt, who referred to him as a “crank”. Odds are he would have preferred occasionally bumping into his more genial son in-law, Emily’s husband William Douglas Sloane, when entering or leaving his own home, than “the crank”.

The Two Elder Sons

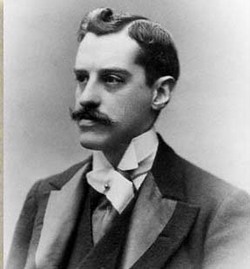

Cornelius Vanderbilt II

Cornelius Vanderbilt II William Kissam Vanderbilt

William Kissam Vanderbilt

At the same time the double palace for William Henry and the two older girls was rising on the block front below, at 660 Fifth Avenue on the southwest corner of 52nd street, pale limestone walls of a Loire chateau were rising in delightful contrast to the surrounding brownstone edifices.

660 Fifth Avenue Designed by Richard Morris Hunt for William Henry’s second oldest son William Kissam (and perhaps just as importantly, his socially ambitious wife Alva), this storied mansion is remembered to this day as one of the iconic mansions of New York’s Gilded Age, host to the legends of Alva’s assault on the “four hundred”, star quadrilles and Mrs. Astor’s capitulation. It should be noted the money for this house came to Willie K not from his father, but from the same will contested so hotly by his aunts and uncles. Having decided that William Henry was to be his principal heir, the Commodore also provided handsomely for William’s two older sons. William K received a 3 million dollar legacy from his grandfather, which funded the construction of 660 Fifth Avenue. Farther up the Avenue about the same time, an even larger legacy left to his older brother Cornelius Vanderbilt II was being used to construct a palatial home at 1 West 57th street.

660 Fifth Avenue Designed by Richard Morris Hunt for William Henry’s second oldest son William Kissam (and perhaps just as importantly, his socially ambitious wife Alva), this storied mansion is remembered to this day as one of the iconic mansions of New York’s Gilded Age, host to the legends of Alva’s assault on the “four hundred”, star quadrilles and Mrs. Astor’s capitulation. It should be noted the money for this house came to Willie K not from his father, but from the same will contested so hotly by his aunts and uncles. Having decided that William Henry was to be his principal heir, the Commodore also provided handsomely for William’s two older sons. William K received a 3 million dollar legacy from his grandfather, which funded the construction of 660 Fifth Avenue. Farther up the Avenue about the same time, an even larger legacy left to his older brother Cornelius Vanderbilt II was being used to construct a palatial home at 1 West 57th street.

1 West 57th Street Designed by Society architect George Post, the mansion marked the northern end of “Vanderbilt Row”. Equally as large as 660, it is also more ponderous and heavy, befitting the sober Cornelius and his equally serious wife Alice. While almost unimaginably grand upon its completion, the home was significantly expanded, into imperial proportions after William Henry’s death, when Cornelius became unimaginably wealthy in his own right. It is the later enlarged version of the home, facing the Plaza that is more familiar to students of New York’s Domestic Architectural history.

1 West 57th Street Designed by Society architect George Post, the mansion marked the northern end of “Vanderbilt Row”. Equally as large as 660, it is also more ponderous and heavy, befitting the sober Cornelius and his equally serious wife Alice. While almost unimaginably grand upon its completion, the home was significantly expanded, into imperial proportions after William Henry’s death, when Cornelius became unimaginably wealthy in his own right. It is the later enlarged version of the home, facing the Plaza that is more familiar to students of New York’s Domestic Architectural history.

The Two Younger Daughters

Florence Vanderbilt Twombly

Florence Vanderbilt Twombly

William Henry also commissioned John Snook to design town homes for his two younger daughters, Florence Vanderbilt Twombly, and Lila Vanderbilt Webb at 680 and 684 Fifth Avenue, between 53rd and 54th Streets.

680 and 684 Fifth Avenue There is less written about these homes. While perhaps not as architecturally distinguished as some of those built by and for their siblings, there facades a vitality and interest to them, and the mix of building materials sets them apart from the uniformity of their neighbors’ homes. In terms of size, they were on a similar scale to their older sisters’ mansions, and I am willing to bet the two younger daughters were quite content.

680 and 684 Fifth Avenue There is less written about these homes. While perhaps not as architecturally distinguished as some of those built by and for their siblings, there facades a vitality and interest to them, and the mix of building materials sets them apart from the uniformity of their neighbors’ homes. In terms of size, they were on a similar scale to their older sisters’ mansions, and I am willing to bet the two younger daughters were quite content.

The Two Younger Sons

Frederick William Vanderbilt

Frederick William Vanderbilt  George Washington Vanderbilt

George Washington Vanderbilt

Frederick (William Henry’s third son) had nearly been disinherited by his father. He had the misfortune (in his parents eyes) or, the good fortune (in his own) to fall in love with Louise Torrance, a woman twelve years his senior. While less than common for the era, it was excusable. What was not however, was the fact that this woman was a divorcee. Her former husband being Frederick’s first cousin didn’t help matters either. So certain it was that his father to be unhappy over the match, that Fredrick decided to keep their marriage under wraps. William Henry not being informed until months after the fact. It took quite a bit of feather smoothing to calm the old man down. Not surprisingly, Frederick did not receive a brand new home from his father the same time as his siblings. No tears need be shed however. Upon completion of his palace at 640 Fifth Avenue, William Henry gifted Frederick and his bride his own old Fifth Avenue home at 459 Fifth Avenue.

459 Fifth Avenue While perhaps not regal, it was still a very impressive mansion by any contemporary standards. The house , though still well within the fashionable residential district of Fifth Avenue, it was also sufficiently south of the new Vanderbilt row, lest the happy couple forget.

459 Fifth Avenue While perhaps not regal, it was still a very impressive mansion by any contemporary standards. The house , though still well within the fashionable residential district of Fifth Avenue, it was also sufficiently south of the new Vanderbilt row, lest the happy couple forget.

That left only William Henry’s youngest child, George Washington Vanderbilt, without a home of his own. While his older brothers and sisters were having new homes built up and down the avenue, stretching the boundaries of fashion and setting new architectural standards for the elite of New York to follow, George was in his teens. When his father passed away in 1885, he was only 23 years old, and still living at home. As such, the young man became the lucky owner of his father’s palace 640 Fifth Avenue, his mother (with whom he was very close, retaining life tenancy.

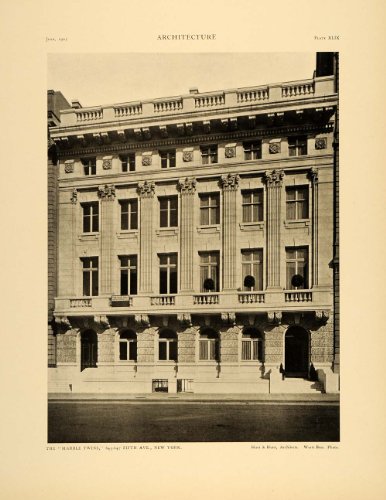

640 Fifth Avenue Upon receipt of this mammoth architectural gift (and mammoth fortune to go with it) George made few alterations to his parents former home (although he did leave his mark on Vanderbilt Row by erecting a pair of townhouses known as the marble twins across the street later on).

640 Fifth Avenue Upon receipt of this mammoth architectural gift (and mammoth fortune to go with it) George made few alterations to his parents former home (although he did leave his mark on Vanderbilt Row by erecting a pair of townhouses known as the marble twins across the street later on). The Marble Twins, designed by Hunt and Hunt For GW Vanderbilt His architectural focus was elsewhere. Although design and construction would not commence for several more years, perhaps he was already dreaming of his future home. A chateau which would one day rise in the mountains somewhere, dwarfing all of his siblings homes in scale and scope - the mythic Biltmore.

The Marble Twins, designed by Hunt and Hunt For GW Vanderbilt His architectural focus was elsewhere. Although design and construction would not commence for several more years, perhaps he was already dreaming of his future home. A chateau which would one day rise in the mountains somewhere, dwarfing all of his siblings homes in scale and scope - the mythic Biltmore.